We are so lucky to have discovered Jessica Raimi.

Here is a perfect summer read reprinted by permission!*

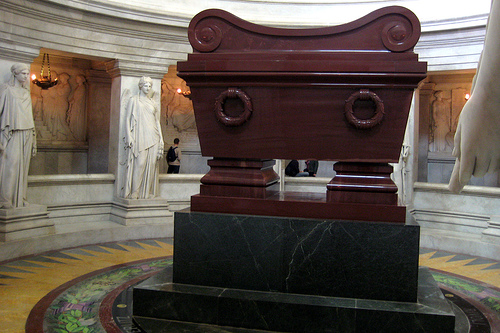

| Beneath the gilded dome of the Invalides in Paris lie the bones of Napoleon. The fallen emperor is protected by six concentric coffins within a sarcophagus, in a crypt adorned with statues commemorating his career. ”The majesty of the setting perfectly befits the Emperor’s image,” says the Michelin guide.

But part of Napoleon is in a less secure facility. A recent letter to the New York Times Book Review, responding to a review of John Vernon’s Peter Doyle, revealed, “The novel’s subject matter — a quest for Napoleon’s amputated penis — is more accurate than Mr. Vernon or [the Times reviewer] realized. Napoleon‘s penis was removed from his body by the surgeons attending at his death [and] is now owned by a surgeon at the Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center.” The custodian of Napoleon‘s manhood is Dr. John K. Lattimer ’35C, ’38P&S, who chaired Columbia’s urology department for 25 years before “retiring” in 1980. (He continues to teach and see patients.) He acquired the item a few years ago, when a collection of Napoleoniana was broken up. |

he says, and the Squier Urological Clinic’s collection at the medical center seemed an appropriate setting.

Lattimer has long been interested in medicine as history. After serving in World War II, he was one of the physicians assigned to care for war criminals tried at Nuremberg. “Our job was to keep them alive until they could be hanged,” says Lattimer, who is writing a book on the subject. The author of Kennedy and Lincoln: A Medical and Ballistic Comparison of Their Assassinations, he also owns the bloodstained collar from the shirt Lincoln was wearing when he was assassinated, as well as a fragment of the car seat John F. Kennedy was sitting on at his death.

|

Dr. Lattimer has nonmedical interests, too. His collection of silver-headed swords will be shown at the Metropolitan Museum this fall, and the Englewood (N.J.) Historical Society published his This Was Early Englewood: From the Big Bang to the George Washington Bridge.

How did the Napoleon relic escape entombment with the rest of him? When Napoleon was dying in exile on St. Helena in 1821, he knew the doctor treating him, a fellow Corsican, was waiting to do his autopsy. “Napoleon was spitting on him, casting aspersions on his sexual capacities -generally being obnoxious,” says Lattimer, so the doctor took revenge. “During autopsies in the tropics, the stench is terrific. There wouldn’t have been any witnesses.” Napoleon’s severed member is not preserved in a jar.

|

*The Little Corporal, by Jessica Raimi, was first published in Columbia Magazine, in 1991.

I imagine it speaks to our shared capacity for leadership!

…very nicely put together – I had to look to see if things had been made up…

[…] The Little Corporal! – 06/17/2016 […]